Quick Wiki

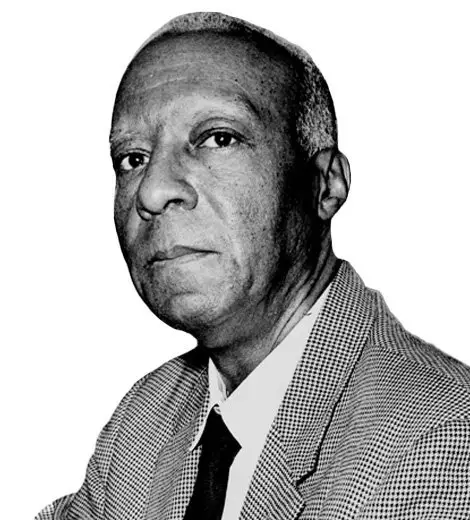

- Full Name Asa Philip Randolph

- Occupation Civil Right Activist, Unionist, Politician

- Nationality American

- Birthplace Crescent City, Florida, USA

- Birth Date April 15, 1889

- Place Of Death New York City (home)

- Death Date May 16, 1979 (age 90)

Quotes

Asa Philip Randolph | Biography

Founder of Brotherhood of Sleeping Car PortersAsa Philip Randolph was the country’s most well-known advocate for black working-class rights. With President Franklin D. Roosevelt refusing to sign an executive order prohibiting discrimination against black workers in the defense industry, Randolph called for a march on Washington, D.C., in December 1940. His popularity increased so swiftly that he soon called for a 100,000-strong march on the capital.

Asa Philip Randolph was an American labor leader who founded and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first organized African-American labor union. He was the prime motivator of the March on Washington movement held in 1963. The movement sought to end employment discrimination in the defense industry and launched a nationwide civil disobedience campaign against injustices to African Americans.

Randolph relentlessly represented the interests of African Americans at the forefront of the racial discourse throughout his work period.

Who was Asa Philip Randolph?

A civil rights activist, unionist, and socialist political figure, Asa Philip Randolph was born in Crescent City, a city in Florida, USA, on 15 April 1889. He was a trade unionist and civil-rights advocate who acted prominently as a leading figure in fighting for African-American justice and equality.

His groundbreaking initiatives persuaded the next generation of civil rights activists that nonviolent protests and mass demonstrations were the most effective means of mobilizing the public’s opinion.

Randolph rose to prominence as the country’s most well-known advocate for black working-class concerns. He had called for a march on Washington, D.C. in December 1940, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt refused to sign an executive order prohibiting discrimination against black workers in the defense industry.

He was promptly and supported mainly for the cause to the point he was ready to convene 100,000 marchers in the capital. Eventually, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was under pressure to act, signed an executive order on 25 June 1941, six days before the March, declaring, “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

He was also instrumental in the military’s integration. He organized the League for Nonviolent Civil Disobedience Against Military Segregation movement, which pushed young men of all races to refuse to serve in a Jim Crow conscription service. The movement then resulted in a threat of mass civil disobedience for President Harry Truman, who then ordered the termination of military discrimination as soon as possible on 26 July 1948.

Early life

Randolph was born to a tailor and ordained preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, Rev. James William Randolph, and a skillful seamstress, Elizabeth Robinson Randolph. T in Crescent City. The family relocated to Jacksonville in 1891, accommodating themselves to a strong and well-established African American community there.

While growing up, Asa carried much learning from his parents. He learned about the supremacy of a person’s character and conduct over their skin color from his father. At the same time, his mother instilled the value of education and the virtue of violence in the dire situation of defending and protecting oneself. The learning grew empathetic when he encountered his mother guarding their house with a loaded firearm while his father hid a pistol under his coat and fled to prevent a mob from hanging a man in the local county jail.

Asa was the second child of his parents and had an elder brother, James, with whom he grew up and excelled in school. They both went to Cookman Institute in East Jacksonville, which was Florida’s only academic high school for African Americans for a long time. Asa was valedictorian of the 1907 graduating class and portrayed immense accomplishment in literature, acting, and public speaking while graduating.

He also played baseball for the school and performed solos with the choir. Later after graduation, he took over various jobs and spent his time singing, performing, and reading. W.E.B. Du Bois’s book The Souls of Black Folk’ was the primary factor that persuaded him to prioritize social equality more than nearly everything else.

Having chances at just manual jobs due to the raging racial discrimination in their locality, the Randolph family relocated to New York in 1911 for better opportunities. Randolph wanted to pursue a career as an actor, but he dropped out after failing to gain his parents’ approval and again started doing odd jobs; he worked as an elevator operator, a porter, and a waiter while honing his rhetorical skills.

Parallelly, he attended City College. He amplified his intellectual horizons by reading economic and political literature, notably Marx, with a hectic schedule of working during the day and studying at City College at night. This theoretical foundation led him to see the black working class as the main hope for black progress rather than the black elite.

Early Career

Randolph made one of his first significant political moves in 1912 when he co-founded the Brotherhood of Labor with Chandler Owen, a Columbia University law student who had socialist political ideologies such as Randolph, to organize Black workers. Randolph also initiated a rally against the miserable living conditions of Black workers while working as a waiter on a coastal steamship.

Randolph married Lucille Green in 1913 and soon after managed Ye Friends of Shakespeare, a drama society in Harlem. He would go on to play a variety of roles in the group’s eventual productions. Additionally, Randolph also joined the Socialist Party and began lecturing the people on socialism and the significance of militant class consciousness at Harlem’s soapbox corner (135th Street and Lenox Avenue).

During World War I in 1917, Randolph and Owen founded The Messenger, a political magazine.

Messenger

Around January 1917, William White, the then president of the Headwaiters and Sidewaiters Society of Greater New York, requested Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph to edit Hotel Messenger, the society’s monthly publication. ‘The Messenger’ became known as one of the most superbly edited periodicals in the history of American Negro journalism after Randolph and Owen withdrew the titular ‘Hotel’ from the masthead and founded The Messenger.’ The political magazine released its first issue in November 1917.

Owen and Randolph eventually began writing articles requesting that more Black people be included in the armed services and the defense industry and emphasizing equal pay and compensation. During this period, Randolph also attempted to organize African American shipyard workers in Virginia and elevator operators in New York City. Following the United States’ entry into World War I, The Messenger advocated for more Blacks to be employed in the military and defense industries. Later, Randolph also lectured at New York’s Rand School of Social Science after the war and sought for the government on the Socialist Party platform, but was unsuccessful.

The magazine provided a platform for individuals such as Randolph and Owen, who were critical of both the NAACP’s (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and Marcus Garvey’s led movement. Randolph and Owen, by this time, were well-established members of the Socialist Party in New York. In 1918, the two embarked on a statewide anti-war speaking tour in 1918. This tour drew the attention of the US Department of Justice and nearly resulted in their arrest.

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

In June 1925, a cluster of Pullman porters, the all-black Pullman sleeping car service staff, confronted Randolph and asked him to plead their cause. With the staff’s support, Randolph then founded Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, their new union. In addition to his long-standing interest in and knowledge of labor unions, Randolph’s primary qualification as the leader was his dedication to African American causes. Adding to that, he was not a Pullman Company employee, which meant he could not be fired or bought off.

Randolph eventually led a grueling campaign to organize the Pullman porters for the next ten years. His efforts led to the BSCP’s (Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters) certification as the Pullman porters’ exclusive collective bargaining agent in 1935. According to Randolph, it was the “first victory of Negro workers over a great industrial corporation,” according to Randolph. At a time when half of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) affiliates refused to include black workers, he was able to have his union accepted into the AFL.

Despite opposition, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porter won its first significant contract with the Pullman Company in 1937. In protest of the AFL’s failure to combat prejudice within its ranks, Randolph later withdrew the union from the organization the following year and joined the newly established Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

In 1968, he resigned as president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and retired from public life due to a persistent illness.

March on Washington DC

Randolph was the country’s most well-known advocate for black working-class rights. With President Franklin D. Roosevelt refusing to sign an executive order prohibiting discrimination against black workers in the defense industry, Randolph called for a march on Washington, D.C., in December 1940. His popularity increased so swiftly that he soon called for a 100,000-strong march on the capital.

Later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was under pressure to act, passed legislation on 25 June 1941, six days before the March, saying that “no discrimination in the employment of workers in military industry or government may be made based on race, creed, color, or national origin.” To oversee the directive, Roosevelt established the Fair Employment Practices Commission.

To successfully express the needs of black workers to the labor movement, Randolph established NALC (Negro American Labor Council) in 1959. Later, Randolph and the NALC organized the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. During this march on 28 August 1963, Martin Luther King Jr delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. The march brought over 200,000 people who were there to show support for Black civil rights. Once again, Randolph was leading an important movement similar to 1941.

Other Civil Rights Movement

Randolph was also vocal on integrating the armed forces six years later, after the passage of the Selective Service Act of 1947. He created the League for Nonviolent Civil Disobedience Against Military Segregation, urging young men of all races to “refuse to engage with a Jim Crow conscription service.” Eventually, President Harry Truman, under threat of mass civil disobedience and in need of the African American vote in his 1948 re-election campaign, ordered the elimination of military discrimination as soon as possible on 26 July 1948.

The March on Washington campaign, as well as Randolph’s demand for civil disobedience to eliminate military segregation, helped persuade the next generation of civil rights activists that nonviolent protests and mass rallies were the most effective means of mobilizing public pressure. Randolph was deemed the genuine “father of the civil rights movement” by many activists in the United States in this sense.

In 1955, Randolph was chosen as the newly combined vice president of The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations(AFL-CIO). As an integral part of the initiative, he utilized his position to advocate for desegregation and civil rights both within and outside the labor movement. From 1960 until 1966, he was the president of the Negro American Labor Council, which he co-founded. Additionally, President Lyndon B. Johnson recognized him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964 for his significant contributions to justice and social equality.

Philip Randolph Institute

Clayola Brown has served as the president of A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI) since 2004. Randolph was the father of the modern American civil rights movement and the prominent black labor leader in the history of America.

Randolph along with Bayard Rustin, a leading civil rights and labor activist, formed an alliance between the labor movement and the civil rights movement. They acknowledged that blacks and working-class people of any color share the same objectives: social and political freedom and economic justice.

This Black-Labor Alliance contributed to the civil rights movement to obtain one of its significant victories- passage of the Voting Rights Act, which eliminated the last existing legal barriers to wide black political participation.

Inspired by this triumph, Randolph and Rustin established A. Philip Randolph Institute in 1965 to resume the struggle for political, economic, and social justice for every working American.

A. Philip Randolph Institute is a Black Trade Unionists organization that works in the areas of economic justice and racial equality. The institute strives to form and consolidate bridges among labor and communities of color.

The institute supports civil rights, strong anti-discrimination measures, affirmative action, and workplace diversity, policy to promote a fair wage, labor law reform, and worker health and safety protections, decent minimum living standards for everyone, including poverty alleviation programs. Similarly, the organization also backstops affordable health care, public education, and labor leadership training and education.

'A. Philip Randolph: A Life in the Vanguard'

This book was written by historian Andrew E. Kersten. Throughout this book, Kersten explores the labor leader’s notable influences and accomplishments as both a civil rights and labor leader. Kersten stresses much towards the political philosophy of Randolph, his engagement in the labor and civil rights movements, and his commitment to uplift the lives of American workers.

Composed of 184 pages, this book was published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers in 2006.

Quotes

1. “At the banquet table of nature, there are no reserved seats. You get what you can take, and you keep what you can hold. If you can't take anything, you won't get anything, and if you can't hold anything, you won't keep anything. And you can't take anything without organization.”

2. “Men often hate each other because they fear each other; they fear each other because they do not know each other; they do not know each other because they cannot communicate; they cannot communicate because they are separated.”

Contributions

Without Randolph, the historic August 1963 Washington March wouldn’t have been possible. He is the one who paved the way for Martin Luther King, Jr as Randolph was the person who dreamt of such a march for more than two decades. On 22nd June 1963, the 35th US President John F. Kennedy invited various civil rights leaders for a meeting in Washington. During the meeting, Randolph presented his idea to gather hundreds of thousands of people at the nation’s capital. “Mr. President, the black masses are restless and we are going to march on Washington '', Randolph told Kennedy. At that point, Kennedy was worried as the march could also lead to violence and chaos. However, Randolph convinced the president by asserting that the march would be an orderly, peaceful and nonviolent protest.

A month before the historic march, Randolph not only brought together six civil rights leaders but also brought civil rights to that point. According to Norman Hiss, the staff coordinator for the march, the six civil rights activists chose Randolph as the director of the march as it was only Randolph who could hold the six of them together.

King delivered the famous 18-minute speech during the march in Washington. Besides King there were other speakers and speeches as well, starting with the opening remarks from Randolph.

Executive Order 8802

Before the 1963 march on the capital, Randolph had three smaller marches in the 1950s for integration of school and also made plans for one in the 1940s that never took place.

In 1941, when the black community was restricted to hold a job in the defense industry, Randolph traveled across the country and rallied potential marchers with the message: “We loyal Negro American citizens demand the right to work and fight for our country.”

Randolph issued a statement, where he explicitly addressed that propaganda shouldn’t be formed and spread to the effect that black communities seek to hamper defense. Also, no charge could be made that blacks are attempting to hurt national unity. A part of the statement said, “Certainly there can be no national unity where one-tenth of the population are denied their basic rights as American citizens.”

As plans for the 1941 march escalated, President Franklin D. Roosevelt invited Randolph to the White House and asked him to call off the march. In return, Randolph asked the president to issue an official order that would allow black people to work in the defense industry. The president refused at first but eventually agreed to issue an executive order, prohibiting racial discrimination in the government and defense industry. President’s executive order 8802, 25th June 1941, established the Committee on Fair Employment Practices to receive and probe complaints of discrimination and apply necessary measures to redress genuine grievances.

Wife

Randolph’s wife Lucille Campbell Green Randolph passed away in 1963, just before the march in the capital. Randolph desired her to see the march.

Mrs. Randolph was trained as a schoolteacher at Howard. Before tying her knots with Randolph, she was married to Joseph Green, a law student. After the demise of her first husband, she quit teaching and enrolled in Lelia Beauty College. After her graduation from her first class at the academy, she ventured into her own beauty salon on 135th Street, attracting aristocratic clientele. Her successful business would support her future husband, massively in his activist projects.

Personal life

In 1914, Randolph married Mrs. Lucille E. Green, a widow and a Howard University graduate who had entrepreneurial ventures. She shared the same socialist political ideologies as Randolph and earned enough money to support them both financially. The couple didn’t have any children.

Resignation And Death

Randolph, who had served as president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters for more than 40 years, resigned in 1968 due to a heart problem and excessive blood pressure. He also stepped down from the public eye. He then relocated from Harlem to New York City’s Chelsea area after being mugged by three assailants.

Randolph, who had never been interested in worldly possessions or property ownership, spent the next five years writing his memoir until his health deteriorated and forced him to quit.

Randolph died in his New York City home on 16 May 1979, at the age of 90, in his bed. His ashes were deposited at the A. Philip Randolph Institute in Washington, D.C., after he was cremated.